Gross Anatomy

Feeding Time

Following Up

Conclusion

Frequently Asked Questions

Errata and Clarifications

Appendix: More Magazines

More articles

Discuss this article at

Feeding Time

How all these magazines looked was really irrelevant if it made no difference in how they performed. Fortunately, it made a difference, enough of a difference that I was able to capture it on camera. Before continuing on, please read this post on controlled feed principles on the M1911.org forum. If you've ever wondered why 1911s don't use a one-piece feed ramp, how hollowpoints contribute to jams where ball ammo does not, or why people who know the 1911 burst blood vessels in their eyes when they hear someone suggest polishing the feed ramp, read that thread. Then you can pop ocular capillaries, too.

Controlled feed is the 1911's greatest strength and greatest weakness; when parts are in spec, the controlled feed mechanism produces an autoloader that can be fired from any angle with almost any ammunition while producing revolver-like reliability. The downside is that magazine design plays far more of a role in reliable operation than in other guns. It's not really fair to say 1911s are magazine-sensitive, though, since few other guns can boast the range of magazine designs inflicted on the 1911. Recent complaints about the M9's unreliability under desert conditions have widely assigned blame to the cheap aftermarket magazines provided, and I suspect even the vaunted Glock reliability would transmogrify into the 1911's jam-o-matic reputation if Glocks were also saddled with the expectation they would feed from anything capable of being jammed into the magwell.

As an aside, in the time since writing the above paragraph, I've learned more about the issue with M9 magazines in Iraq. Check-Mate was responsible for manufacturing these magazines at the behest of the Army, who requested a corrosion-resistant parkerized finish. However, the rough phosphated finish tended to trap the super-fine sand found in Iraq, leading to problems with the magazines. According to a Check-Mate representative, Check-Mate Industries was unable to find the source of the problem until they actually acquired some Iraqi sand and were able to reproduce the phenomenon. My experiences with Check-Mate's magazine quality has been nothing but positive; both the Colt hybrid and Springfield OEM magazines examined in this writeup turned out to have been made by Checkmate.

For the purposes of demonstration, I've used magazines loaded with three rounds of ball ammo. Three rounds is the sweet spot in 1911 magazines, where the top round is not under the maximum tension as when it's fully loaded; nor does it face the special feeding case of being stripped off the follower instead of a round beneath it. By using three rounds, these photos will show the magazines under their ideal functioning conditions.

First up is the most common type of 1911 magazine found today: the "wadcutter" style magazine, so named because its parallel feed lips and sudden release point proved helpful in feeding semi-wadcutter rounds in 1911s. This style of feed lips results in feeding that is an exaggeration of the controlled feed principle: The round slides forward almost horizontally under the influence of the feed lips, forcing the bullet into the frame ramp. As the bullet slides up the frame ramp, the rear of the cartridge suddenly releases, hopefully sliding up the breech face and under the extractor fast enough to relieve the angle at which the cartridge pivots over the edge of the frame barrel. If the rear of the round doesn't get released in time, there's the danger of a stem bind, where the rim of the cartridge binds up under the extractor, preventing the round from being fully chambered. Stem binds can usually be fixed by shoving the slide into battery; however, their nasty cousin, the three-point jam is not so easily remedied. A three-point jam occurs when magazine and barrel ramp geometry conspire to let the bullet strike the barrel ramp too low. Instead of having the bullet slide over the lip of the chamber, holding the barrel down, the bullet forces the barrel to cam up slightly, raising the angle at which the cartridge enters the chamber and prematurely jamming the barrel's lugs into the slide. The feeding round gets wedged solid between the ogive of the bullet at the roof of the chamber, the cartridge at the edge of the barrel ramp, and the rim under the extractor.

Of the seven magazines available to me, three of them had the wadcutter-style feed lips and flat or convex followers: the Metalforms (both rounded and flat followers) and the Colt magazine with the dimple-less follower. All their photos looked almost identical, so I chose the pictures taken with the Metalform magazine with rounded follower as they provided the most representative examples.

A round dips out of a Metalform magazine into the frame ramp.

The actual declination of the dip is relatively shallow.

Note the dip into the frame ramp in the above two photos. It's fairly mild but enough to ensure the round jumps from the frame ramp to the barrel ramp, as show below.

After riding up the frame ramp, the bullet pivots over the lip of the chamber.

The same pivot from above.

Next, I tested the Colt hybrid mag. This one requires some backstory.

The original design for 1911 magazines calls for a flat, dimpled follower with a leg bent into it; so far we've seen that type of follower design on the Springfield, Colt hybrid, and one of the Metalforms. What none of the mags feature are the fully-tapered feed lips that widen from the base to a release point well forward of where wadcutter magazines release. The result of this design is to turn the nose-down/nose-up gyrations seen in the Metalform photos above into a much subtler wiggle.

Unfortunately, I don't think anyone makes magazines like these anymore, but I can guess why. These magazines are sometimes referred to as "hardball" magazines after the ball ammo they were designed to feed. I would suspect that the fact they released relatively late and high could lead to problems in out-of-spec guns when trying to feed hollowpoints or wadcutters, tainting that particular magazine design with a reputation for use only with ball ammo, and who would want to shoot just ball out of a 1911? All of the above is pure speculation on my part, but I'm told that an in-spec 1911 will function best with any round given an original design USGI tapered-lip magazine.

But this is all academic because nobody makes these magazines anymore. We have the next best thing, though, in Colt factory hybrid magazines. These mags completely release the round eventually, but the feed lips up to that point are tapered, allowing the cartridge to rise higher before the release. The amount of taper is fairly dramatic: The magazine I used went from 0.37" in the rear to 0.42" immediately before the release point.

The net effect of the taper, as mentioned above, is to make the dip into the frame ramp very subtle, too subtle to get a good photo. I was able to take a good shot of the round nosing over the barrel ramp, though.

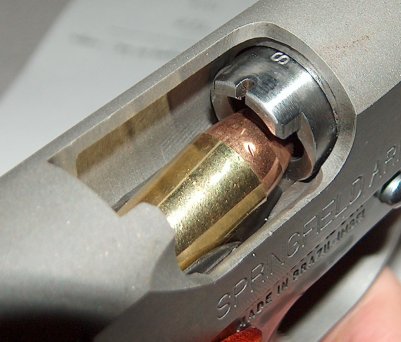

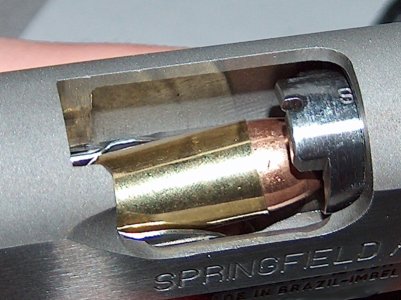

Colt hybrid mag chambering.

Getting a real rise out of this round.

Notice how much milder the angle is compared to the wadcutter mags above? The second photo also shows that the tapered lips let the entire cartridge rise higher before entering the chamber, keeping the three points of contact well away from the point where they would result in a jam.

I was interested to see if any of these principles came into play with Wilson magazines. Wilson 47Ds have a reputation for reliability, and I'd heard that they held the round relatively high.

Lining up the shot.

As you can see, the round is held much higher relative to the chamber than any other magazine other than the Colt hybrid. The Wilson mag has straight lips and a full-length grooved follower, though, which results in the round taking a straight shot at the chamber. No dip into the frame ramp, just a bump over the barrel ramp and into battery.

Just a hop, skip, and a jump away.

These photos show the bullet's meplat approaching the barrel ramp edge, but not quite touching it. The reason I don't have any photos of that is because the Wilson's feed lips let go of the rim either at the instant the bullet touches the barrel ramp or less than a hundredth of an inch before. (I couldn't tell for sure.) What I can tell you, though, is that it's definitely not a controlled feed. The rim of the cartridge pops up with great alacrity, and if the slide isn't moving forward fast enough the rear of the case will bypass the extractor entirely and the entire cartridge will zip merrily out the ejection port before a photo can be taken. Above a certain speed this doesn't happen, of course, and the cartridge just hops right into the chamber.

I now know why Wilson mags can appear to fix three-point jams. In situations where an out-of-spec frame or barrel ramp causes premature barrel cam-up due to bullets hitting the barrel ramp too low, Wilson mags' habit of bypassing controlled feed also bypasses the point in the feeding process where the jam is generated. Nothing's free, though, and the cost in this case is a mechanically guaranteed feed; instead, the last little pop into battery is accomplished by the grace of inertial forces alone. I'd be interested in seeing how well 47Ds hold up to firing from strange angles or with jostling, but lack the thousands of rounds of ammo it would take to perform a statistically rigorous analysis.

The next magazine up was the Colt magazine with the flat follower. The front of the follower had felt a little unsupported to me, so I was interested in seeing if that made any difference in feeding.

Yep, it made a difference.

The follower's front collapsed as the straight feed lips forced the rear of the cartridge down, permitting the largest amount of dip into the frame ramp of any of the rounds I tested. As the round was pushed farther forward, though, the ramp guided the bullet up and let it tip over the barrel in a smooth, controlled manner.

It's like the feeding of the round is controlled by the shape of the gun or something.

The Para-Ordnance magazine, with the channel on the front of its follower, led me to believe that it would experience a lot of dip into the frame ramp, but I was surprised to see that its angle of approach was pretty much the same as the others.

Note absence of extreme dip.

However, the tipover into the chamber was one of the most extreme of all the magazines tested. It looks like the groove at the front of the follower is allowing the front of the rounds to dip down slightly under the pressure of the feeding cartridge's rim, which lowers the rim and causes the funky feed angle seen above.

High tipover angler from the Para mag.

Finally, the Springfield OEM magazine was something of a surprise. Although it appeared to be a standard wadcutter design, it turned out that its lips had a slight 0.39" to 0.41" taper. This shows in the photos, which appear to split the difference between the Colt hybrid and the other wadcutter mags.

Springfield Armory OEM mag feeding toward chamber.

Note relatively high and level feed into chamber.

Summary

Magazines with the wadcutter-style feed lips (Metalforms, flat-follower Colt) demonstrated controlled feed, but not very elegantly. Wadcutter lip designs operate at the edge of the controlled feed parameters, but if the gun and ammo are well within their own specifications, this shouldn't be a problem.

The Colt hybrid mag was everything its reputation made it out to be. Its tapered feed lips didn't alter the fundamental feeding mechanism, but let the cartridge rise up in the process. By smoothing out the extreme motions seen in wadcutter mags, the hybrid magazines provide a little more leeway for variations in bullet shape and gun dimensions. Chambering felt smoother and slicker, as well.

The Wilson 47Ds turned out to be really educational and I'm glad I got a chance to see how they work. They cleverly short-circuit a part of the feeding process commonly associated with three-point jams. This is only accomplished by losing control of the round right before the gun goes into battery, though; whether someone considers this acceptable is really a personal choice.

Where the Wilson magazine flipped the bird to controlled feed, the flat-follower Colt magazine with wadcutter lips illustrated the value of this feed scheme. Even though the follower collapsed in front during the feeding process, the cartridge was brought under control and chambered normally.

I took measurements of each magazine's feed lips. I've only included them where applicable because for the most part they were very similar, with only hundredths of an inch of variation in dimensions. For such small measurements, though, the difference in the way the gun felt while chambering round from different magazines was palpable. I couldn't capture it in photographs or even on video; it has to be felt to be understood, and I'm grateful I was given the opportunity to do so.

But I'm not done yet.

email: hidi.projects at gmail.com